Statistics and the Johns Hopkins Gun Study

February 19, 2014This week, the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health alongside the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research announced the forthcoming release of a study linking the repeal of Missouri’s Permit to Purchase (PTP) handgun law with an increase in the state’s murder rate. The report, set to be released in a coming issue of Journal of Urban Health, claims that since the 1921 law’s repeal in 2007, the homicide rate in Missouri has increased and that the absence of such a law has accounted for an additional 55 to 63 murders per year. Given this claim, I had to dig into the issue.

First of all, it should be noted that the study claims to ‘control’ for factors such as poverty, incarceration, and unemployment. Unfortunately, given the report’s unreleased status, it is impossible to determine exactly what is meant by this. As a society, we cannot even fully agree on how to quantify these issues, much less fully account for them statistically. We must also remember that firearms policies do not exist in a vacuum. That is, a combination of several factors can influence crime rates in a given area, and how these rates might change over time can also be affected by the same variables. To presume that anyone fully understands the causes of crime well enough to control for all but firearms policy is an extremely lofty assumption.

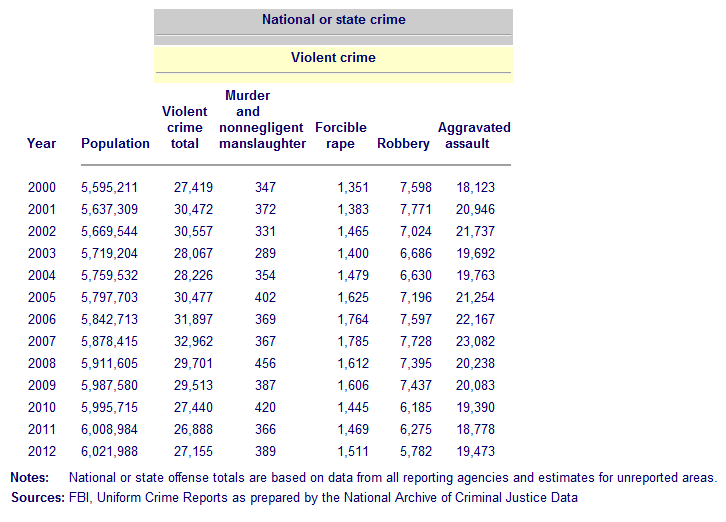

With the above disclaimer and understanding, we do not currently know the study’s methodology; it is still possible to address the study’s claim head-on. As I said before, the study asserts that murder rates increased after the PTP law’s 2007 repeal, to a tune of more than 55 additional murders per year. Unfortunately for this ‘unbiased study,’ the truth does not seem to support the school’s claim. The table below was sourced from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports. As many readers are likely to realize, the UCR are generally considered the most accurate reports of crime data within the United States.

According to the UCR, the homicide rates appear to have remained remarkably steady within Missouri since 2000. In fact, total homicides have shown no notable increase while the population has increased by nearly 500,000 people over this period. Based on this knowledge, it would be reasonable to argue that Missouri homicide rates have actually decreased over the past several years. However, that is not the aim of our discussion today.

A deeper dive into the statistics reveals some interesting points about violence in Missouri. Though the PTP law dates back to 1921, FBI UCR data only goes back to 1960. Still, this should give us a good basis for comparison. With this in mind, I went back and regenerated the table to fetch entries from 1960 to 2012. Based on this data, I was able to determine that the average homicide rate from 1960 to 2007 (the year the law was repealed) was 8.11 incidents per 100,000 residents. This time period exhibited a standard deviation of 1.96. The fact that a single standard deviation makes up almost one-fourth of the total means that the homicide rate in Missouri fluctuates considerably.

After looking at the period prior to the law’s repeal, I turned my attention to the five years following the end of the law. From 2008 through 2012, the homicide rate in Missouri averaged 6.76 incidents per 100,000 residents. Contrary to the study’s claim, the homicide rate has actually dropped following the law’s repeal. A link to the Excel file with the full data can be found below.

Google Drive Doc

After analyzing the UCR statistics, I felt that it would still be important to try to understand how the study came to such a conclusion. Without having access to the study, I approached the issue with the null hypothesis (working assumption) that the law’s repeal had no effect on crime rates. This was chosen because the alternative hypothesis (that the law did reduce homicide rates) is much more difficult to assess, given the lack of post-repeal data. I will spare readers a discussion on p-values in this article as I feel the results of our analysis are telling enough, and we can come to a conclusion without invoking further statistical evaluation. The post-repeal data exhibits an average of 1.36 fewer incidents per 100,000 residents each year. The fact that this difference is not only within a single standard deviation of the pre-repeal mean but also lower than the mean for the period prior to the PTP law’s repeal is notable. Using typical research practices, in order to reject the null hypothesis, post-repeal homicide rates would need to average at least two standard deviations higher than the pre-repeal mean. Based on the information available, it seems that the Johns Hopkins researchers fell prey to a remarkably egregious type I error (improperly rejecting the null hypothesis), damaged the data in ‘controlling’ for other factors, used an improper null hypothesis, to begin with (perhaps by using our alternative hypothesis), or some combination of these factors.

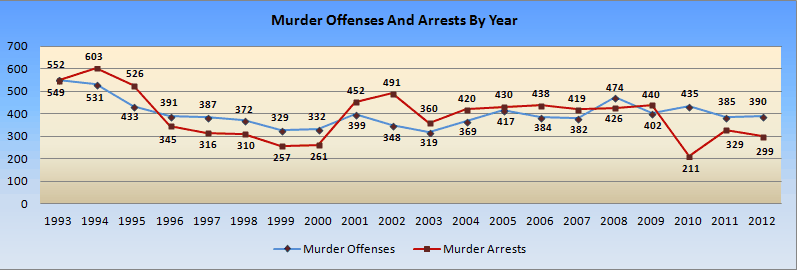

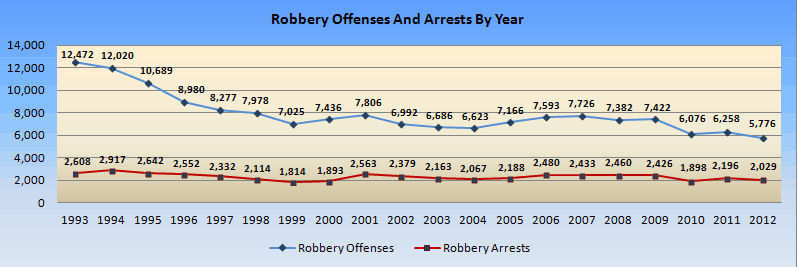

Furthermore, Missouri State Highway Patrol data supports our conclusions. The graph featured below was sourced from the MSHP’s Statistical Analysis Center. As we can see, the number of murder offenses committed each year has remained very steady over the past several years, though arrest numbers have varied wildly. As we can see, 2010 was a particularly bad year for policing in Missouri.

Some readers may be asking, “why are the numbers in the UCR and MSHP data different?” In short, this is likely because the underlying reporting used to generate the data can often be incomplete or inconsistent. As such, final numbers are close approximations of crime levels for a given year. These numbers should not be taken for their precision, but should be viewed as good estimates. This makes the Johns Hopkins claim even more dubious given the level of precision that the study seems to assume.

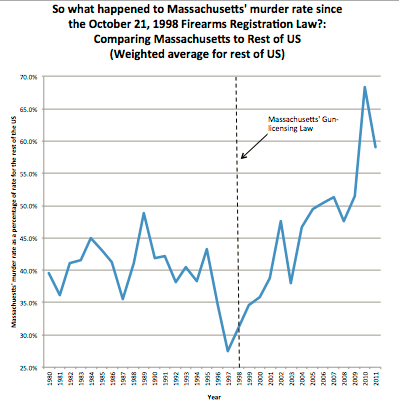

So what does all of this mean? According to former University of Chicago and Yale University professor, Dr. John Lott, the study’s conclusion does not mean much at all. In his critique, Dr. Lott highlights that the researchers at Johns Hopkins had to cherry-pick data to fit their conclusion. In other states, the results of such licensing schemes have yielded much different results. One example that Dr. Lott highlights is Massachusetts, where just prior to the law’s passage, the state’s murder rate was less than one-third the national average. In just ten years after the law took effect, the state’s murder rate nearly doubled as compared to the national average.

Lastly, we have to consider the source of this ‘study’. Johns Hopkins is a school that has deservedly gained substantial attention worldwide for its remarkable medical programs. The university is undoubtedly at the top of many aspiring doctors and researchers’ lists. Still, we must not let this reputation cloud our common sense and good judgment when addressing this misguided piece set to be published by Johns Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health.

As some readers have probably realized by now, the Bloomberg aspect of the school’s name is indeed the result of a $1.1 billion donation from fanatical anti-gun crusader and former New York City mayor, Michael Bloomberg. Last year, New York’s most famous control freak and junior despot made this massive donation so that the university could make numerous campus improvements, including the construction of a school of public health. According to a NY Times report, $250 million of the donation was to be used to hire 50 new researchers. Lead author of this most recent study, Daniel Webster, has even published a book, Reducing Gun Violence in America, with a foreword by Michael Bloomberg. To say the study is ‘unbiased’ is incredibly disingenuous.

While the study set to be released by Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health is certain to present itself under the guise of unbiased professionalism, a critical analysis of the study reveals serious holes in its claims. The assertions made by the study simply do not reflect reality in Missouri and are based on some very questionable statistics. Furthermore, the school’s credibility as a policy research center is completely destroyed by its relationship with fanatic Michael Bloomberg. While it will be worthwhile to read through the whole study, readers should embark upon this task with extreme skepticism.

Study announcement: eurekalert

UCR data: RunCrimeStatebyState

MSHP data: crime_data_violent_crime

Lott on Massachusetts: massachusetts-murder-rate-has-risen

NY Times on donation: at-1-1-billion-bloomberg-is-top-university-donor-in-us

Webster book: Reducing-Gun-Violence-America-Informing

Jeremy Mallette is co-founder of International Sportsman. An avid hunter and outdoorsman, he has spent more than a decade in the outdoor industry, from hiking and camping to silencers and hunting. His father taught him to shoot at age six, and he received his first firearm at age eight — a 1942 Colt Commando .38 special revolver. He enjoys yearly trips to Kansas for pheasant hunting, spending time with his children at the deer lease, and collecting unique firearms.

An information security professional by day and gun blogger by night, Nathan started his firearms journey at 16 years old as a collector of C&R rifles. These days, you’re likely to find him shooting something a bit more modern – and usually equipped with a suppressor – but his passion for firearms with military heritage has never waned. Over the last five years, Nathan has written about a variety of firearms topics, including Second Amendment politics and gun and gear reviews. When he isn’t shooting or writing, Nathan nerds out over computers, 3D printing, and Star Wars.