How Roller-Delayed Firearms Work and Why it Matters

Ten years ago, I made what was arguably the worst firearm purchase of my then-young firearm collecting life. You see, I’d always loved the classic Heckler & Koch G3. As a child of the 90s, I grew up playing games that featured the rifle – Rainbow Six and Battlefield 2 come immediately to mind – and in each one of these, few weapons kicked ass like the G3. So naturally, I wanted the closest approximation I could find.

At the time, even the PTR line of G3 clones was too spendy for my college freshman budget, so I settled for a widely criticized alternative from Century Arms: the CETME. Like a bad relationship, I learned a lot from that rifle and also like said relationship, I probably should have heeded advice and warnings ahead of time. In short, the rifle was improperly assembled with a ground bolt, no bolt gap, and it required enough force to charge that I could take a week away from the gym after loading a few magazines. Though I never bothered to bring the rifle to perfect functionality, the experience taught me loads about roller delayed blowback actions. All was certainly not lost as this knowledge regularly serves me well as the present owner of both a PTR-91 and my favorite personal firearm, a Zenith Z-5RS MP5 pistol.

Background

As firearm designs go, roller-delayed or roller-locked actions aren’t new. The MG42 and MG3 family of machineguns may be the most famous in this lineage. However, there’s a difference between roller locked and roller delayed. In a roller locked system, like the MG42, the barrel recoils as the gun cycles. Roller delayed firearms use fixed barrels and, thanks to this simplicity, are more common in modern weapons. For that reason, this article will focus on roller delayed designs, leaving a detailed look at roller lockers for another day.

To understand why roller delayed blowback is significant, it’s vital to first examine the incumbent of sorts – simple direct blowback operation. In a direct blowback system, a heavy bolt and (usually) a heavy spring are the only components keeping the chamber sealed when in battery and after firing. The heavy bolt is necessary to provide the proper inertia. When a chambered round is fired in a direct blowback firearm, the initial chamber pressure is not sufficient to overcome the inertia of the at-rest bolt. As pressure behind the fired (but still in the barrel) round builds, eventually the bolt starts to retreat, ultimately opening the chamber, extracting/ejecting the spent casing, and retrieving another round from the magazine.

The upsides of direct blowback operation are its simplicity and reliability. It’s possible to make workable direct blowback designs very cheaply and they should perform well even in adverse conditions. There’s a reason, after all, why Hi-Point can sell their firearms for bottom dollar.

Unfortunately, the system’s downsides are numerous. The heavy bolt makes for a lot of reciprocating mass during operation. This, in turn, brings increased felt recoil and muzzle flip. Moreover, while direct blowback guns are generally reliable, the bolt and spring weights are tuned for very specific conditions. Modifying barrel length or, more commonly, adding a suppressor significantly impacts shooting experience with these firearms as both force the chamber to open at a higher point on the pressure curve. What does that mean in practice? Faster cyclic rate (more recoil) and port pop, a phenomenon where pressurized gas escaping from the chamber causes a loud pop and undermines the effectiveness of suppressors.

How it Works

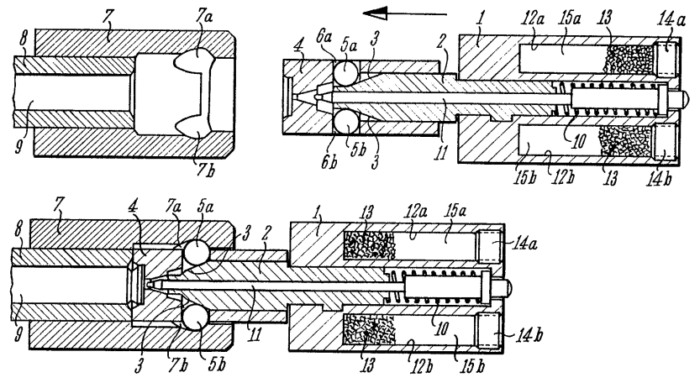

Roller delayed blowback is the answer to many of these concerns, but not all. So how does it work? Take a look at the diagram below from an official HK tech drawing.

From right to left, you have the barrel (8), the trunnion (7), the locking piece (2), and the rollers (5a/5b). The graphic also includes a separate denotation for the locking piece’s engagement surfaces (3). Other notable parts are the bolt head (4) and the carrier (1). There are, as you can see, other parts in this area, but they don’t play enough of a role here to justify inclusion.

When a round is chambered in a roller delayed gun, the bolt head fetches it off the magazine and pushes it into the barrel’s chamber just like any other firearm. The locking piece follows the bolt head and, upon reaching battery, pushes the rollers into recesses (7a/7b) machined into the barrel trunnion. This is the locking action that is definitive of the system. At this point, the chamber is effectively locked shut against anything but very high pressure.

Touching off a round kicks off an impressively choreographed set of actions that make these guns special. Like direct blowback systems, roller delayed firearms lack a gas system, relying entirely on pressure buildup behind the bullet traveling inside the barrel. As that pressure increases, it pushes harder and harder against the face of the bolt. This causes the bolt to want to travel rearward, but thanks to the now-trapped rollers, it can’t budge. The wedge-shaped locking piece backed by a heavy carrier spring has firmly planted the rollers inside the trunnion recesses.

Eventually, the pressure reaches a breaking point. The rollers, now sufficiently strained, push against the angled engagement faces of the locking piece from both sides, forcing the piece to slide rearward like a wet bar of soap. Now, the rollers can retreat into the bolt head and clear the trunnion to make way for the now unlocked bolt head to finally open and unseal the chamber at a much lower pressure level than was present when this dance started.

Is it Better?

The advantages of roller delayed actions are significant. First, the lighter bolt assembly and reduced bolt velocity mean that felt recoil and muzzle rise are almost non-existent, particularly in pistol calibers and compared to straight blowback. Generally, roller delayed firearms suppress far better than direct blowback as well. By slowing the action, the roller system waits until chamber pressure begins to taper before opening. The result is diminished port pop and superb at-ear performance. Few subguns suppress anywhere near as well as the MP5 and that’s thanks to its roller delayed operation.

Moving up to centerfire rifle calibers complicates the roller delayed story. It’s also where the design’s advantages begin to diminish. Against popular piston and direct impingement systems, delayed blowback is saddled with some serious disadvantages. Remember, blowback guns rely on chamber pressure to operate. There is no gas system to tune. This means that variations in ammunition pressure, barrel length, or adding a suppressor significantly affect cyclic rate on a roller gun. Sure enough, these also present challenges for competing designs, but their gas systems either self-regulate (to a degree) or can be tuned to match the situation.

The best a roller delayed system can do is swap for a different locking piece to extend lockup time. That’s because the angle of the locking piece’s engagement surfaces determines how much force is needed to move the part. Thus, a more acute angle extends lockup while an obtuse one allows the breech to open sooner. Swapping locking pieces requires at least partial bolt disassembly and is not exactly something that’s ideally done in the field.

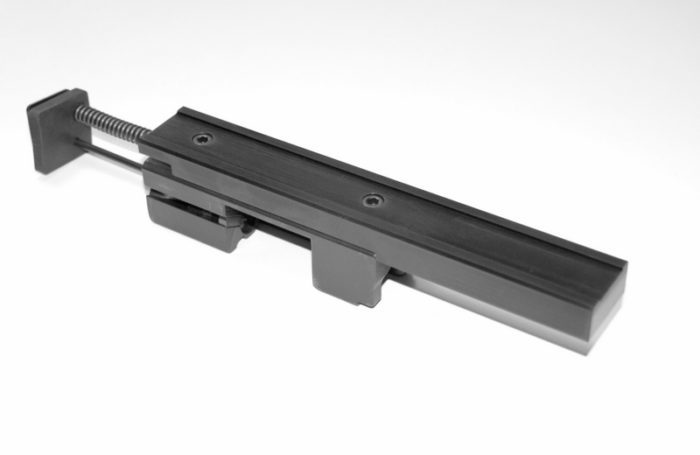

The other major disadvantage faced by roller systems is something known as bolt gap. Bolt gap is the distance between the rear of the bolt head and the carrier, measured with the hammer down. Proper spacing between these parts (usually between 0.010” and 0.020”) is critical to time the action. As parts (particularly the locking piece and rollers) start to wear, this gap decreases. If it ever reaches zero, the roller delayed firearm may become a single-shot rifle as too much pressure is needed to push the locking piece rearward. Other designs have similar wear parts, but roller delayed systems are graced with more parts that could potentially cause these sorts of issues. If you’re curious as to what all of this looks like, the video below is perhaps the best explanation of the bolt gap I have seen yet.

I’ve ragged on roller guns with centerfire rifle cartridges quite a lot over the last few paragraphs, so let’s shift to the positives. Once the relevant tuning is complete, these rifles rise to the top as suppressor hosts. After suffering numerous failures to feed and harsh recoil with a suppressor mounted to my PTR-91, I decided to swap the original 45-degree locking piece for the famous #17 36-degree part. The reduced-angle piece allows my rifle’s breech to stay closed noticeably longer and restores suppressed and unsuppressed functionality to 100% with greatly reduced recoil. Moreover, because the PTR (and other HK-style rifles) isn’t gas-operated, gas blowback is non-existent. There are ways to modify an AR or similar rifle to mitigate the bursts of hot gas to the face after each suppressed round, but such changes aren’t necessary on a roller delayed firearm.

In addition to being superb suppressor hosts, roller delayed rifles possess fewer breakage-prone parts. The bolt sports no lugs, has no rotational mechanism, and features no breakable stem or pins. Extractors and springs go out on occasion, but it’s hardly unique to this design. Catastrophic failures that can’t be blamed on ammunition are extremely rare with properly assembled roller systems.

In the end, roller delayed actions represent a massive improvement over simple blowback in virtually every respect. They’re compatible with a wider range of cartridges, are more configurable, offer less recoil, and support suppressed shooting far better than straight blowback. For pistol-caliber carbines and submachine guns, roller actions have very few true rivals. With rifle cartridges, roller delayed systems’ lead evaporates to a significant degree as piston and direct impingement actions encroach on or surpass once-exclusive advantages. Even so, certain applications, such as suppressed shooting, leave ample room for roller actions to flex their muscles.

An information security professional by day and gun blogger by night, Nathan started his firearms journey at 16 years old as a collector of C&R rifles. These days, you’re likely to find him shooting something a bit more modern – and usually equipped with a suppressor – but his passion for firearms with military heritage has never waned. Over the last five years, Nathan has written about a variety of firearms topics, including Second Amendment politics and gun and gear reviews. When he isn’t shooting or writing, Nathan nerds out over computers, 3D printing, and Star Wars.