The Australian Gun Control Experiment

When discussing gun laws, supporters of further restrictions have a tendency to point to other nations as examples for why gun control works. As was established in The Folly of Cross-Cultural Comparisons, this paints a woefully incomplete picture of the issue. That said, one of the token nations for the gun control effort continues to be Australia.

Following the 1996 Port Arthur shooting, the Australian government moved quickly to impose a sweeping set of new gun laws aimed at removing virtually all popular long arms from civilian possession. As part of the 1996 National Firearms Act, the Australian government raised A$500 million in its efforts to “buy back” more than 631,000 firearms that had been legally held by civilian gun owners. Despite the fact that the Port Arthur shooter, Martin Bryant, had not obtained his firearms in a legal manner (did not possess the required license), hundreds of thousands of legally-owned firearms, many of which were family heirlooms, were rounded up through Australia’s forced buyback.

With this background in mind, we need to look at whether or not the 1996 NFA has had any real effect on homicide and violent crime rates within Australia. Keep in mind that when doing so, we must look at the issue from a before and after perspective and must avoid making cross-national comparisons so that we may maintain a consistent definition for what is considered a violent crime. Though suicide rates are often irrelevant to the gun control discussion, as is evidenced by nations like Japan, we will also venture into some recent studies regarding suicide rates to determine whether or not the 1996 laws have had any significant effect on suicides in Australia.

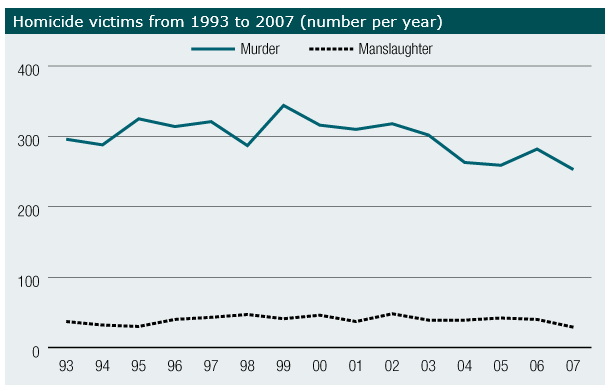

The first noteworthy statistic that must be considered as part of this analysis is the homicide victimization rate. The Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) has provided the data below for homicide victimization. Keep in mind that over the course of this study, the mean population of Australia increased somewhat (from 17 million to 20 million). Still, in the years prior to and after 1996, we see no major change in the number of reported murders. Were the gun control effort such a resounding success, we would expect to see a sharp decline in the years after the 1996 NFA. Instead, the number of reported homicides has remained relatively constant each year, and only recently can a slight decline be found.

Further, when looking at the weapons used in homicide incidents, we see an interesting trend. Though homicide by firearm has been on a general decline since well before the 1996 incident, homicide by sharp object has increased at almost a mirror pace. Looking at the data, we can see that nearly every year that gun-related incidents dropped by a significant amount, there was also a substantial increase in sharp object deaths. This seems to establish some serious legitimacy for the replacement theory, or the idea that alternative methods will be adopted by criminals who desire to bring about harm.

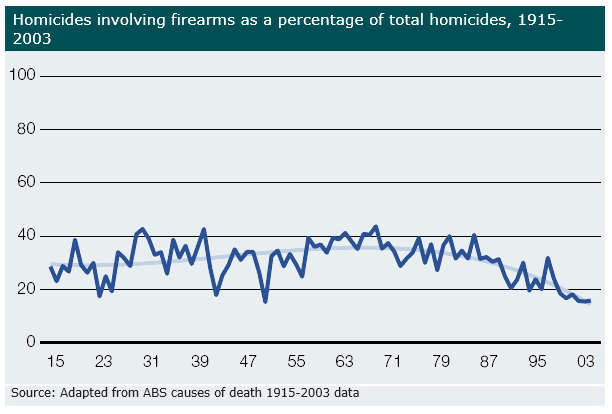

Further, AIC data from the past century seems to indicate that the current low levels of firearm-related crime have been experienced before. Indeed, the variance for this data is significant enough to raise some serious doubts as to whether the current rates will be sustained. It should also be noted that there appears to be no statistical basis for the ‘best-fit’ line, as seen in the below data.

In the years since 1996, there has been substantial discussion as to whether the NFA has had any significant impact on suicide rates. Three major studies (Wang-Sheng & Suardi 2010, ACE-Prevention 2010, McPhedran & Baker 2012) have all concluded that the NFA has had little effect on suicide rates in Australia. The ACE-Prevention study clearly states that the gun buyback was excessively expensive while the McPhedran and Baker study highlights that “restriction in the form of firearms legislation could not be tied to a corresponding impact on youth suicide.”

Next, we must consider the cost of the Australian buyback. The collection of the approximately 600,000 legally owned firearms was undertaken at a cost of approximately A$500 million, or approximately A$833 per firearm. Not all-expense was tied to reimbursement, but the per firearm marginal cost appears to have been quite high, especially by 1996 standards. Some estimates of private gun ownership in the United States place total civilian-held firearms in the 300 million range. A similar buyback in the US would cost well into the hundreds of billions of dollars even without factoring for inflation. In an interesting parallel to the current American debate, those who opposed the registration of firearms in Australia were labeled paranoid. Apparently, they had good reason to be worried.

Lastly, we must take a closer look at some recent reports regarding illegally owned firearms in Australia. According to Sydney Police, there is evidence to suggest that the decade-long decline in firearm-related murders may be coming to an end. As of January 2013, Sydney Police have reported substantial increases in drive-by shootings and ruthless execution-style killings as compared to previous years. Police in Sydney are concerned that they may be seeing an increase in the number of deaths resulting from petty arguments and targeted killings. Police Commissioner, Nick Kaldas, has even gone on record as saying, “[w]hether it’s young men or others in criminal groups, they are getting access to guns.” The Australian Crime Commission estimates that there are nearly 300,000 firearms in the nation’s black market.

After serious consideration, it appears that the Australian gun control experiment has failed to bear the sort of fruit that many gun control advocates seem to assume. Overall, homicide rates were already steadily declining prior to 1996, and the trend appears to have continued in more recent years. Further, firearm-related homicides have historically been relatively uncommon in Australia. While there has been a general decline in firearm related homicides in recent years, an almost equal increase in homicides by sharp object has been apparent, and general violent crime rates have increased substantially since 1996. Lastly, no scholarly consensus exists with regard to the NFA’s effect on suicide rates. With the above considerations in mind, it appears that Australian gun control efforts have been largely unsuccessful in substantially reducing crime.

References (in order of usage):

transcript-police-interview-martin-bryant

An information security professional by day and gun blogger by night, Nathan started his firearms journey at 16 years old as a collector of C&R rifles. These days, you’re likely to find him shooting something a bit more modern – and usually equipped with a suppressor – but his passion for firearms with military heritage has never waned. Over the last five years, Nathan has written about a variety of firearms topics, including Second Amendment politics and gun and gear reviews. When he isn’t shooting or writing, Nathan nerds out over computers, 3D printing, and Star Wars.