Vittles Et!

“Mmmmm! You gotta taste this!” said Tim Fallon as he handed me a large, filled crystal bowl. The bottom contents appeared to be a grayish milky liquid, topped with a foamy gruel substance. “Beer, brewed daily!”

Not being opposed to trying different “foods,” I raised the bowl to my lips and used my teeth to sieve out the “mash” and took a drink. I have never tasted diesel fuel mixed with vinegar, but after tasting the “local beer,” I thought I had a pretty good idea of what that combination might taste like!

The second time around, I raised the bowl to my lips, but this time pretended to take a drink. To have refused their “beer” would have been considered an insult by our hosts.

Next on the menu was a boiled domestic sheep’s head. Our host spoke in the local dialect. Then using a spoon, removed the eyeballs. He placed them on a small silver platter and cut them into strips. These were ceremoniously presented to my hunting partners Tim Fallon, Ken D’Arcy, and me. We were told these would help us have “the proper vision” to see ibex once we were high in Kyrgyzstan’s mountains. I had eaten sheep eyeballs before while hunting in Africa. Eyeballs, to me, were and are the only part of a domestic sheep that I considered edible. I wouldn’t say I like meat from domestic sheep regardless of the age, size, or whence it comes. I have tried lamb/mutton throughout the world after comments such as “You may not like lamb or mutton, but you’ve never had it the way we prepare it!” Be that as it may, I have never found anything made from the flesh of a domestic sheep to my liking, no matter how it is disguised.

But minutes later, so as not to offend our hosts, I ate boiled mutton with figurative relish, hiding my gagging by coughing. I have to, however, admit it was fun watching my hunting partners eat boiled sheep without the benefit of any seasoning!

The boiled domestic sheep meat was locally considered a delicacy. I was really glad I had previously drunk the “diesel and vinegar” daily brewed beer to help kill the flavor, but then wished I had taken that second swallow, nay two or more.

Our boiled sheep encounter did not end there. After horse-backing many miles into the mountains for our ibex hunt, we realized the only meat packed in with us was…left-over boiled domestic sheep! That hunt was memorable in many ways, including a lack of any game in the area, but also because of our “interesting” camp cuisine.

Over the past fifty-plus years as a hunter/conservationist, wildlife biologist, outdoor writer, and television show host, I have spent a fair amount of time in hunting camps worldwide, absorbing the local culture and trying local foods.

On hunts, I have dined on elegant meals served on the finest of china, silver, and crystal on down to the most basics of simply “eating,” like having to eat raw fish to stay alive. The latter, years ago, I “experienced” while stranded in the Arctic for several days. I had my essentials: a one-person tent, sleeping bag, knife, ultra-light spinning rod, reel, and four Mepps spinners.

Unbelievably dense fog prevented others from flying and moving base camp to where I had been dropped to scout a likely area. Thankfully the stream I was camped beside was loaded with Arctic grayling. I could catch one every cast.

While I enjoy sushi, I admit that when the fog finally cleared and my fellow goose-banders could fly in with groceries, I was thrilled. After a week of having nothing to eat but raw grayling, I was ready for a dietary change!

Africa has beckoned me numerous times, sometimes twice a year. I fell head over heels for Namibia, the country previously known as South West Africa. Fred Burchell, with whom I often hunted, was a great professional hunter and a fabulous naturalist. European museums of natural history often sent representatives to Fred’s hunting operation to collect nearly anything that swims, slithers, crawls, walks and flies. Regardless of the animals collected, Fred had his skinners save the meat. He would then have his cooking staff prepare it for us to “try.” Doing so, I tasted some strange “food items.” But just about everything I tried in Fred’s camps tasted “good.” One of my most memorable meals was made from an aardvark, braised, and then smothered in brown gravy. It had the flavor and texture of veal.

On one of my Namibian safaris with Corne Kruger, who I also often hunted with, we were after an “own use” elephant. “Own use” meaning an older non-trophy bull with small or broken tusks. Such bulls are often “a problem” as well. They frequently destroy the local villagers’ meager crops and homes.

Hunting for an “own-use” elephant is often a most difficult and trying hunt, requiring getting close looks at many bulls. So it’s often frustrating but also always fun. My choice in firearms for my hunt in what used to be called the Caprivi Strip, now known as the Zambezi Strip, was a Ruger M77 .416 Ruger, topped with a Trijicon AccuPoint scope and loaded with Hornady 400-grain DGS Dangerous Game ammo.

We had several encounters with elephants, often with older bulls whose tusks were too large, young bulls full of themselves and anxious to prove their worth, and cows with young who had a chip on their shoulder. Tense moments, great fun, and exciting!

During my early years, I never thought I might one day want to shoot an elephant. But that attitude changed completely during my first hunt in Zimbabwe. No matter where we went, we were charged by tuskless cows and young bulls, barely making good our escape.

The day I shot my Caprivi elephant, we had the night before gotten “intel” about a bull that had eaten nearly all of a local village’s crops and then trampled several homes. Once in their village, we learned it was something he had done numerous times in the past.

We had just gotten on the track of the bull we hoped to take when we were charged by a herd of elephants. We narrowly missed being trampled by hiding behind trees as they ran past us, arm lengths away. Then too, there were miles-long walks and stalks. Elephant hunters or yore often stated, “You kill an elephant with your legs!” meaning taking one requires walking miles and miles of “bloody” Africa.

We finally caught up with the problem bull. He was with a small herd of cows in relatively thick “jess.” We “wove our way” through the herd and crawled past within mere feet of a cow and her calf to get where I could take a shot at the bull.

He was quartered away slightly. Before leaving for my hunt, I had spent considerable time studying elephant anatomy. I knew where to place a bullet no matter the angle faced.

“Shoot the brain, angling in behind his ear,” whispered Corne, ready for a follow-up shot with his .470 NE double-rifle loaded with Hornady’s 500-grain DGS Dangerous Game.

I did as Corne instructed me to do. At the shot, the bull shuddered and started falling. I reloaded and quickly shot him a second time, again shooting for the brain. As the bull fell, Corne shot him through the chest. My bull was down. Immediately Corne grabbled my arm as I bolted in a third-round and pulled me to where I could put a security shot into the bull’s vitals. Then I opened the bolt and began replenishing my now near-empty magazine. “He down!” proclaimed my PH.

“Mistah Vysoon, Congratulations!” said a broadly smiling Corne extending his right hand toward me. A myriad of emotions flooded my mind.

After photos and a bit of quiet time for me to reflect upon my elephant, Corne cut off the bull’s tail and presented it to me, sealing the deal that he was mine. That is when the game guards allowed local villagers, well over a hundred, onto the scene to process the bull. Having been on past “own-use” elephant hunts as an observer, I knew in a matter of very few hours; nothing would remain of the bull. I watched as the locals, using anything essentially with a sharpened edge, butcher my bull. Soon as they started, they also built several small fires. Once through thick skin, the butchers cut little strips of meat which were dropped directly on the fire’s coals. I had seen this done before on other hunts but was never invited to partake of the cooked meat.

“Misthah Vysoon, for you a piece of your elephant.” Said Corne as the local headsman handed me a charred piece of meat. I accepted it. “Thank You!” The village elder nodded.

I scraped ashes and embers off the meat, blew on it to cool, then took a bite. It was tough and stringy, with muscle fibers nearly the size of a pencil. But, it was tasty and good, reminding me remotely of beef brisket.

I am not into “to do” or “have done” lists, but I did check off eating meat from an elephant I had taken.

Tasting meat from different animals has long been something I enjoyed. Years before my first trip to Africa, as a wildlife biologist, I had the opportunity to taste meat from a cougar. It was the texture and color of wild pork and delicious. So it only made sense if I ever shot a leopard; I would definitely want to taste the meat of it as well.

Forward to my taking a huge leopard at the last moment of a hunt with Dzombo Safaris/Japse Blaauw on property adjoining Namibia’s Etosha Park. After skinning my leopard for a full-body mount to be done by Double Nickle Taxidermy, our skinner claimed the carcass. I was told leopard biltong was a highly prized local commodity.

Leaving the following morning, we stopped by the skinning shed where they were making leopard biltong, jerky without any seasoning, i.e., dried meat. The head tracker walked to the drying rack, removed a small strip of leopard meat, and handed it to me, motioning for me to eat. I thanked him and took a bite. It reminded me of cougar and bobcat meat. Had it been flavored with a bit of salt, it would have been delicious.

I have eaten other interesting “vittles,” including some extremely good, such as small braised cubes of African waterbuck (often said to be inedible) cooked over an open flame in Uganda, truly a pleasant and delicious surprise. This, to a bit more questionable items like dried minnows in Burkina Faso to fox and coyote here in North America.

What is the strangest food you have ever “enjoyed” while experiencing local culture?

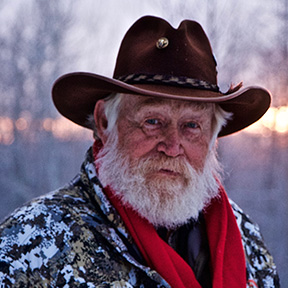

Professional wildlife biologist/outdoor communicator, Larry Weishuhn, known to many as “Mr. Whitetail”, has established quality wildlife management programs on over 12,000,000 acres throughout North American and other parts of the world. He has hunted big game with rifle and/or handgun on six continents. Larry is a Professional Member of the Boone & Crockett Club, life-member of numerous wildlife conservation organizations including the Dallas Safari Club, Mule Deer Foundation, and Wild Sheep Foundation. He currently serves on the DSC Foundation Board of Directors, is one of three co-founders of the Texas Wildlife Association; is a member of the Legends of the Outdoors Hall of Fame and the Muy Grande Hall of Fame; he too, received the Zeiss Lifetime Achievement Award among many other honors.