Recreation and Research Inside the Arctic Circle

Clad in a hat, down jacket, and carpet slippers, a sailor sits cross-legged on the bow of his anchored yacht. In the background, across limpid, wintry water, a low tundra rises, rolling towards the snow-shrouded hills beyond.

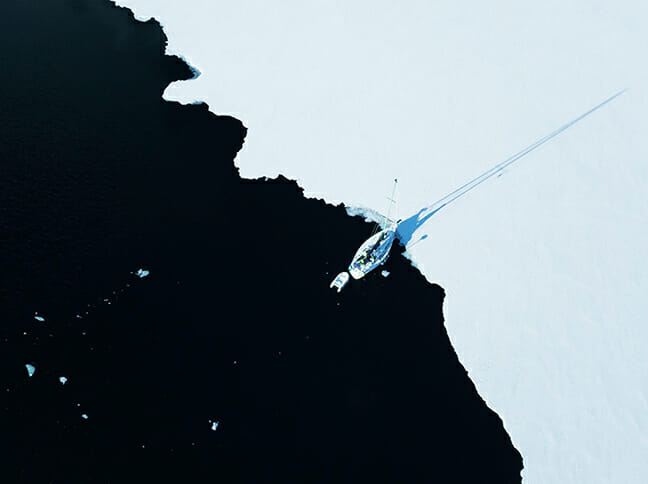

The sailor is Juho Karhu, and the boat a 1986 Beneteau Idylle 11.50 named Sylvia. For the past year and a half, they have been cruising the waters north of the Arctic Circle, at times accompanied by friends.

Juho, 33, grew up in eastern Finland and is a keen skier, having honed his skills while living and studying in Austria and previous visits to the Arctic. “While skiing on the coastal mountains, I always kept looking at the islands further out in the sea,” said Juho. “I could see there was good skiing, but it was inaccessible without a boat.” Sylvia is his golden ticket to sail, kitesurf and ski in some of the most remote spots on the planet.

Juho started sailing at 23, from Finland’s coastal capital, Helsinki. “When I picked up sailing, I got into it and started racing immediately,” he explained. “I spent a season in Sydney sailing a Laser dinghy. I crewed on different kinds of boats, and we also had an active match-racing team which I skippered for two seasons. Although we did train a lot, it was never really that serious.”

But it was the purchase of Sylvia in 2017 that ultimately led to Juho spending two Arctic winters on board a largely unmodified production cruising boat. “Although I did plan to move into it, I did not originally plan to sail to the Arctic when I bought it. But when the idea of Northern Norway and Svalbard came to me, it also quickly became obvious that it would be easiest just to use the boat I already own. Of course, budget restrictions were a part of this, too,” he explained.

Juho moved on board in the spring of 2018 after a punishing few months refitting Sylvia for Arctic sailing. Alongside effecting any maintenance or repairs to the sails, rigging, engine, and other systems, he fitted a diesel stove to the cabin to provide heating in the cold weather, and a careful selection of essential electronics to help him communicate and navigate in the sometimes-hostile waters. “I chose Raymarine, primarily because they’re known for quality equipment that you can trust,” he said. “For me, durability is a top priority. The stuff needs to be as maintenance-free as possible. In the north, I don’t have easy access to maintenance facilities, spares, etc.”

Onboard, Sylvia now boasts an EV-200 linear autopilot pack, a RAY70 VHF with AIS receiver, Raymarine’s Quantum radar, and an Axiom multifunction display. “I did all the installation work myself; in fact, I did all the wiring after already having left Helsinki while we were anchored in the outer archipelago in Finland,” explained Juho. “All are connected to the Axiom multifunction display, which is mounted on a 360-degree rotating base in the cockpit. This allows me to see all the necessary information and also control the autopilot while sailing from one central point. The EV-200 autopilot pack with the linear drive is essential for me since I’m sailing solo most of the time, and then the autopilot is always steering – except when going in and out of the harbors.”

This simple but functional system facilitates single-handed sailing and ensures Juho has the best navigational information available. “Sailing to Svalbard, we had to study the ice maps carefully, especially because we crossed the Barents Sea in May; the normal cruising season begins in July. We sailed through the fjords a few times, but only in calm conditions. The Quantum radar can detect the bigger bits of ice and this is certainly useful, especially because the southern tip of Svalbard is often covered in fog. We experienced this, sailing for two days in very thick fog. Despite the radar it was awful,” he remembered. “Up here in the north, it’s not just the fog that can make your life difficult, but also the darkness and snow flurries,” he continued. “They can very quickly reduce visibility to less than 100 meters.”

For passage planning and as a backup to the Navionics charts on the Raymarine system, Juho uses the SeaPilot app on his mobile phone and tablet. “Up here where things are sometimes badly charted, I use them in combination with the other charts on the Axiom plotter and my computer,” he explained. “I like to have two different sources of map data because inevitably all charts will have some kind of mistakes, so if I’m going somewhere sketchy – a new, badly charted anchorage for example – then I like to check both SeaPilot and Navionics, plus satellite pictures if they are available.”

Sailing in extreme latitudes during the winter months will always pose challenges. According to Juho, “a normal uninsulated fiberglass boat will handle the conditions in northern Norway perfectly well. The only problem can lie within the crew, but so far I’ve done just fine! Things like a snow shovel, and a rubber hammer to knock away the accumulated ice on the deck, do come in handy. During the winter I think I use them more than the winch handles. I’ve had some other small issues with the boat as well, like the mainsail track filling with ice and the toilet hoses freezing, but I’m happy to report that during the past one-and-a-half years above the Arctic Circle I haven’t had any problems with the electronics.”

In between sailing, skiing, and shoveling snow, Juho maintains a blog, several social media channels, and, while in Svalbard, collected snow samples for the Sval-POPs project. The project, which is jointly run by Gdansk Technical University and the Italian Institute for the Dynamics of Environmental Processes, is using snow chemistry to conduct a spatial comparison of the distribution of persistent organic pollutants (POPs). These pollutants are human-made compounds that travel to the Arctic in various ways, particularly from long-range transport, and are already causing significant damage. The Sval-POPs project aims to establish snow sampling as an effective way to measure the distribution of the pollutants, paving the way for future research. Juho’s travel by sea and snow have provided the opportunity to collect samples from locations normally inaccessible to the science team.

Asked about his plans for the future, Juho said: “Next summer I want to transit the White Sea-Baltic canal through Russia, then spend the winter sailing the Baltic Sea. In some ways, this will be more challenging than winter sailing in northern Norway, because large parts of the Baltic tend to freeze during the winter. I might try overwintering in the ice somewhere in the outer archipelago.

“The whole winter in the Baltic will be preparation for the future trips,” he continued. “I have my sights set on ideas like overwintering in Greenland, then transiting the Northwest Passage to Alaska. Overwintering in the ice is not possible in a fiberglass boat, so I’m actively looking for an expedition-style boat that fits my budget. “I’d also like to use my boat more as a platform for scientific research and am currently looking for a Baltic-related project to support next winter.”

Follow Juho’s adventures on social media:

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCDpg-x8jI4T5Kk4h2jE00mQ

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/alluringarctic/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/alluringarctic/