Duck Population Decreases, But Most Species Remain Above Average

North America’s spring duck population declined, but most species remain above long-term averages, according to the 2019 Waterfowl Population Status Report released today.

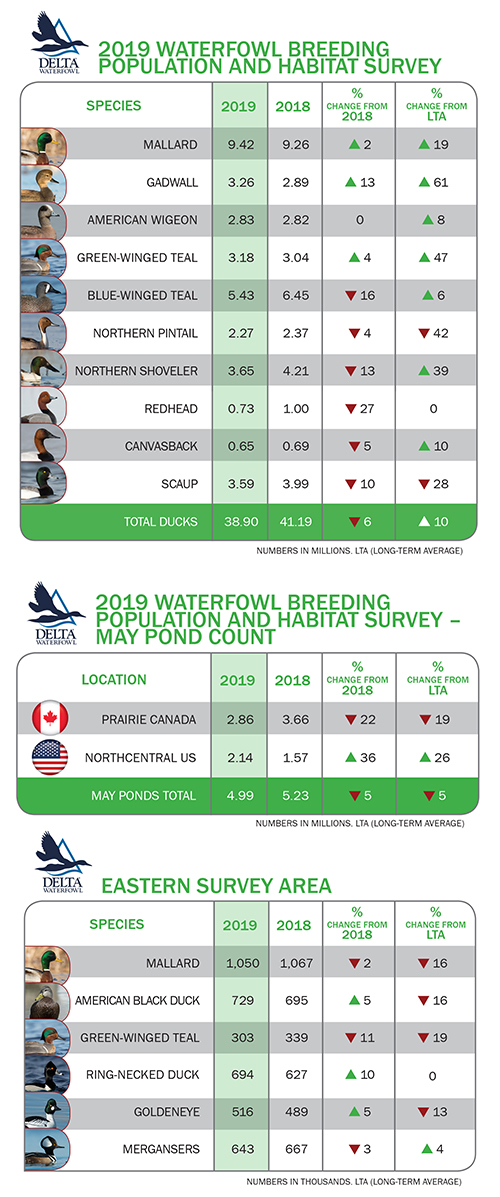

The annual survey, conducted jointly by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Canadian Wildlife Service since 1955, puts the breeding duck population at 38.90 million, a 6 percent decrease from last year’s population of 41.19 million, but still 10 percent above the long-term average. The 2019 survey marks the first time since 2008 that the estimated breeding duck population has fallen below 40 million.

“The fact that the numbers are down is a reflection of last year’s dry conditions for nesting ducks. We know that production drives duck populations, so it’s no surprise that after a year of poor production, the USFWS counted fewer ducks.”

Dr. Frank Rohwer, president of Delta Waterfowl

There is good news to be found in the survey. Mallards increased 2 percent to 9.42 million, 19 percent above the long-term average. (Unfortunately for Atlantic Flyway hunters, mallards decreased by 2 percent in the Eastern Survey Area to 1.05 million.) Green-winged teal rose 4 percent to 3.18 million, 47 percent above the long-term average. American wigeon climbed slightly to 2.83 million, 8 percent above the long-term average.

Notably, gadwalls climbed 13 percent to 3.26 million, putting them 61 percent above the long-term average.

“The real surprise to me is that gadwalls seem to be almost drought-proof,” Rohwer said. “They’re pretty amazing ducks.”

Other dabbling ducks decreased but remained above long-term averages. Shovelers declined 13 percent to 3.65 million, 39 percent above the long-term average. The largest decrease was observed among blue-winged teal, down 16 percent to 5.43 million, but still 6 percent above the long-term average.

“The bluewing estimate makes sense,” Rohwer said. “Bluewings didn’t fare well last spring given the dry prairie and didn’t produce many ducks.”

The only below-average population estimate among puddle ducks is for pintails, which dropped 4 percent to 2.27 million, 42 percent below the long-term average.

“Many pintails settled in the Dakotas seeking better water conditions, as did all ducks,” Rohwer said. “But the core of the pintail’s traditional breeding range is in southern Alberta, where they’re down 79 percent, and southern Saskatchewan, where they’re down 85 percent. More than a million pintails — almost half the breeding population — settled in the U.S. prairie this year.”

All three diving duck species surveyed showed declines in 2019. Redheads fell 27 percent to 730,000, putting them right at the long-term average. Canvasbacks dropped 5 percent to 650,000 but remain 10 percent above the long-term average. And scaup (greaters and lessers combined) declined 10 percent to 3.59 million, 28 percent below the long-term average.

“I’m concerned that bluebills may return to restrictive harvest regulations if their recent population trend isn’t reversed,” Rohwer said. “And we’ve been living off high redhead numbers for a long time, but we just had two average to dry years.”

Across the U.S. and Canada, the May pond count registered 4.99 million — 5 percent lower than last year and 5 percent below the long-term average. Pond counts in the prairie and parkland Canada, which covers Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, decreased 22 percent to 2.86 million, which is the lowest estimate since 2004 and 19 percent below the long-term average. Pond counts in the north-central United States, which covers Montana and the Dakotas, increased 36 percent to 2.14 million, 26 percent above the long-term average.

“This year’s pond count and nesting conditions are truly a tale of two countries,” Rohwer said. “Canada is in bad shape — it started dry and got even drier. I haven’t seen portions of Canada this dry since the mid-1980s. However, the prairies in the Dakotas started wet and stayed ridiculously wet. The problem is that while many of the duck estimates in the U.S. are up, it wasn’t enough to compensate for dry conditions in a region as massive and important to duck as prairie Canada.”

However, Rohwer said production in the highly wet eastern Dakotas region — where mallards are up 54 percent; pintails rose 64 percent, bluewings jumped 19 percent, and total ducks are up 29 percent — has been exceptional. That’s good news for hunters, who shoot the fall flight, not the breeding population.

“The numbers aren’t as bad as they appear,” Rohwer said. “For example, even though bluewings are down, a higher portion of their breeding population than average settled in the wet Dakotas, where they should produce ducklings like crazy.”

Even though breeding duck numbers are down overall, the U.S. prairies were incredibly wet from south to north, which will lead to strong duck production. Conditions remained wet and improved during the breeding season, with temporary and seasonal wetlands retaining water into July and August.

“So, when the prairies were dry last year, it hurt duck production, and in turn, duck hunters,” he said. “We saw it in Louisiana and elsewhere. But this year, ducks nested and renested in the U.S. prairies with a vengeance and should have high brood survival in those landscapes.”

Strong production in the U.S. prairies should also increase the number of more easily decoyed juveniles in the fall flight, compared to the savvy, adult birds many hunters encountered last season.

“There will be plenty of ducks in the fall flight, and I expect duck hunters, especially in the southern U.S., to have a better season this year,” Rohwer said.

Delta Waterfowl is The Duck Hunters Organization, a leading conservation group founded at the famed Delta Marsh in Manitoba, with its U.S. Headquarters in Bismarck, North Dakota. We work to produce ducks through intensive management programs and conservation of breeding duck habitat. Delta conducts vital waterfowl research, and promotes and protects the continuing tradition of waterfowl hunting in North America. Our Mission: To produce ducks and secure the future of waterfowl hunting.